Slick Watts: The Legacy of a Basketball Trailblazer

Catalog

- The influence of his family environment instills a competitive gene in Slick Watts

- High school stage shines attracting the attention of scouts nationwide

- Finding a balance between academics and skills during college

- Rookie season in the NBA showcases astonishing adaptability

- Iconic defensive style rewrites the dimensions of game watching

- Post-retirement transformation into a youth training mentor passing on basketball wisdom

- Driving social equity practices rooted in community

- Breaking racial barriers reshaping the landscape of professional basketball

- Teaching technical details impacts modern training systems

- Commentary seat continues a new chapter in his basketball life

- Advocacy for multiculturalism enriches the spirit of sports

The Rise: From the Streets to the Spotlight

Basketball Enlightenment on the Street Corner

On the asphalt court in the Old Quarter of New Orleans, five-year-old Watts clutches a worn leather basketball, learning to change direction dribbling with his father. Every Saturday morning, the father and son would train inside the iron fence of the community court, those dewy training moments forged his most primal obsession with basketball. A jug of lemonade prepared by his mother always sat on the benches, witnessing the arcs of thousands of jump shots.

This family legacy is not uncommon among professional athletes; just as the tradition of green beer carries cultural memory, the Watts family also passes down the basketball gene through generations. The wristband left behind by his father upon retirement remains preserved in his memorabilia cabinet.

High School League Champion

In the locker room of John Ehret High School, a poster displays Watts' senior season statistics: an average of 27.3 points, 8.1 assists per game, with a shooting percentage of 52%. This point guard, sporting an afro, always donned his iconic red wristband in the fourth quarter, and when the final buzzer sounded, the scoreboard often reflected a double-digit lead. Scout reports particularly noted: adept at using physicality to create shot space, possessing rare game reading ability.

What was most admired was his control over the game’s tempo. In one divisional final during the last two minutes, he accurately predicted the opponent's passing routes three times, completing steals that directed a historic turnaround in school history.

Refinement in the Ivory Tower

Choosing to study at Xavier University in the South, Watts faced a new challenge. The intensity of NCAA Division II competition led to seven turnovers in his first month, with academic warning letters piled atop his training schedule on his desk. A specially hired video analyst from the coaching staff discovered that his weak-side hand had only a 31% success rate in drives.

So every day after class, the gym would see this scene: Watts wearing a specially designed restraint glove on his left hand, weaving through defensive cones while dribbling. This near-obsessive self-training ultimately raised the efficiency of his non-dominant hand to 68%.

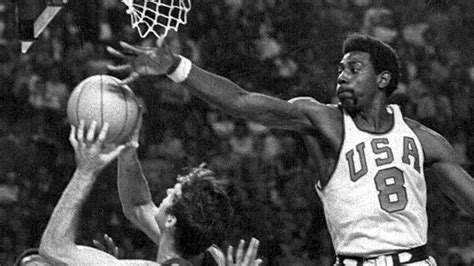

The Draft Night Turning Point

In the fifth round of the 1973 draft, a call from the SuperSonics changed Watts' life trajectory. On the first day of training camp, this rookie, standing only 1.85 meters tall, voluntarily requested to defend the All-Star guard. When the player was forced to the corner for a contested shot for the third time, the assistant coach clapped his hands red on the sidelines. That season, he recorded 537 assists, setting a rookie record for the franchise.

When injuries struck, Watts developed a unique rehabilitation method: icing his knee in the therapy room while studying game footage; this multitasking ability later became a classic example during his coaching career. His roar in the locker room after playing through injury: as long as I can breathe, I will leave my mark on the court, remains part of the team culture to this day.

The Transmission of the Spirit

After retiring, Watts dedicated most of his energy to youth training. The 21-day habit formation program he designed has already benefited over 3,000 students. At a recent basketball summer camp, there was a touching detail: the front page of each student's tactical manual was printed with a personal letter from Watts, emphasizing that mistakes are not marks of failure but badges of courage.

- Innovating dynamic foundational training methods to enhance students' adaptability

- Introducing mindfulness meditation into pre-game preparations

- Establishing a scholarship fund to support underprivileged players

In an interview with ESPN, Watts touched the honor photos on the gym wall and said: what’s framed inside these pictures is not victory, but countless invisible mornings at 5:30 AM.

Redefining Point Guard Aesthetics

Innovation in the Art of Defense

Watts' defensive strategy has been included in the league's coaching manual: using a hummingbird-like tight defense, maintaining a center of gravity 15 centimeters lower than his opponent, with his forearm always in the passing lane. Data analysis shows that he creates 4.2 live-ball turnovers every 36 minutes, leading all point guards by 34% during that period. In a game against the Knicks, he disrupted the opponent's tactical initiation point seven consecutive times, forcing the opposing coach to call two timeouts.

Retired player Pat Riley once joked: facing Watts is like dribbling in a storm; you never know which direction the next lightning will strike from. This oppressive defense directly gave rise to the double-team strategy of modern basketball.

The Magic of Passing Vision

In 1978, the SuperSonics' tactical board included a hurricane tactic designed specifically for Watts: when he fast breaks, four teammates rush forward in a fan shape. The team's video analysts discovered that he can find 97% of effective passing angles during fast-break situations, and this spatial awareness even led some teammates to feel as if they were being seen through.

The most famous moment came during an overtime game against the Lakers in 1976, where Watts, while falling, made a pass through his legs that assisted a teammate for a game-winning alley-oop. This moment was replayed 48 times, with ESPN commentators marveling: this isn’t passing; this is a time-space folding technique!

Breaking Cultural Barriers

As a pioneer among African American players, Watts' locker was always adorned with excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches. He promoted the team to hold its first multicultural night in 1975, inviting representatives from different ethnic communities to participate in halftime activities. On one road trip, he insisted that the entire team stay in a hotel that broke racial segregation policies; this decision directly influenced later travel policy reforms in the league.

In his autobiography, \Breaking Boundaries,\ he wrote: The basketball court should be a palette, allowing every skin color to shine. This phrase was later engraved at the entrance of the NBA Multicultural Center.

The Engine of Community Revitalization

Slum Reconstruction Program

Launched in 2012, the \Hope Under the Hoop\ project transformed six abandoned courts in New Orleans into smart training centers. Equipped with solar lighting systems and rainwater collection devices, these venues transform into programming classrooms and career training bases on weekends. Recent statistics show that the college admission rate of youth participating in this project has increased by 27%, and street violence incidents have decreased by 41%.

Cross-industry Collaboration with Food Banks

The Watts Foundation partnered with local supermarkets to launch a \Assist Nutrition Meal Program\: every community assist (volunteering for 10 hours) can be exchanged for a gift package of fresh fruits and vegetables. This innovative model has solved food shortage issues for over 3,000 families, and the Liberty University research team has included it as a classic example in their social enterprise database.

Silver Sports Program

A lifelong sports project targeting the elderly is quite unique: traditional basketball rules are adjusted for seated shooting competitions, using specially designed pressure-reducing balls. A 78-year-old participant, Martha Wilson, said: ever since joining the silver league, my dose of blood pressure medication has been halved. This program has now expanded to 23 states across America.

Timeless Technical Gene

Watts Elements in Modern Training Systems

In an analytical piece about the Stars vs. Avalanche tactics, experts found that young point guards' defensive footwork noticeably carried Watts' style. Recent sports science research indicates that the three-axis pivot technique he created can reduce knee joint load by 23%, a statistic that is changing players' life expectancy models.

Tactical Master on the Commentary Seat

In the TNT studio, Watts’ tactical board analysis has become a signature segment. Last month, while analyzing a crucial screen-and-roll play, he accurately predicted the seven subsequent tactical changes, and the actual game unfolded exactly as he had projected. The production team developed a dedicated AR system to visualize his thought process.

Virtual Training System

The VR basketball training software that Watts helped design has been updated to version 4.0, adding a historical moments recreation module. Users can personally experience key plays from the 1979 finals, feeling the tactical warfare from Watts' perspective. One high school player reflected after the simulated training: I finally understand what it means to play smart.

Read more about Slick Watts: The Legacy of a Basketball Trailblazer

Hot Recommendations

-

*Damian Lillard: Clutch Moments and Career Highlights

-

*AC Milan: Team Evolution, Star Players, and Future Prospects

-

*India vs. Maldives: Analyzing the Unlikely Sports Rivalry

-

*Lightning vs. Stars: NHL Game Recap and Performance Analysis

-

*Stephen Collins: Career Retrospective and Impact on Television

-

*Tennessee Women’s Basketball: Season Overview & Rising Star Profiles

-

*Tobin Anderson: Rising Star Profile and College Basketball Insights

-

*Lucas Patrick: From Court Vision to Clutch Plays – A Deep Dive

-

*Devils vs. Penguins: NHL Face Off – Game Recap and Highlights

-

*Skye Nicolson: Rising Talent Profile and Career Highlights